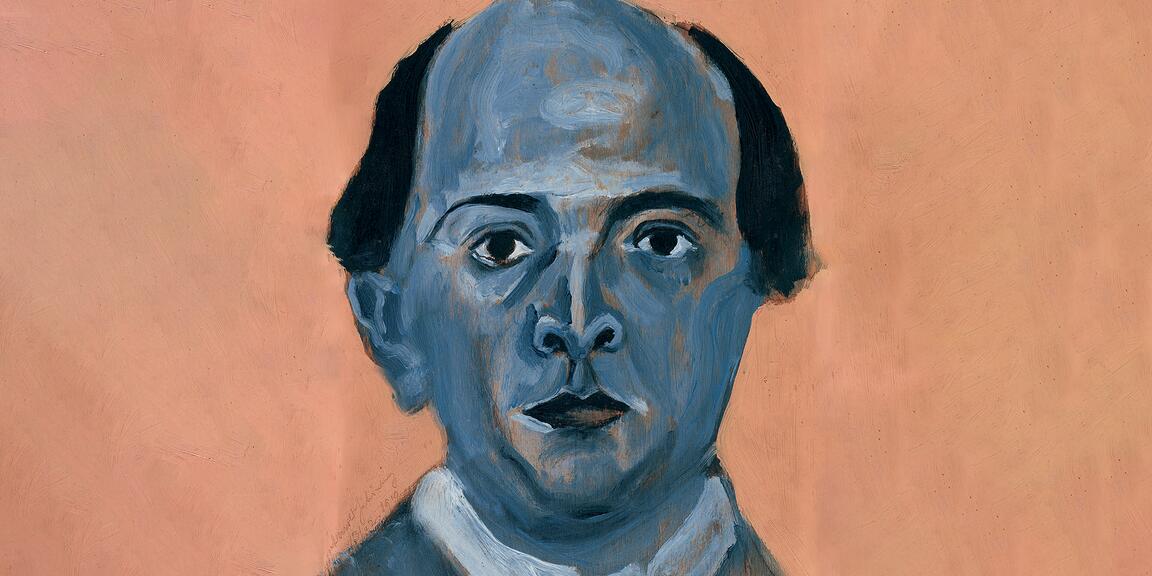

a conversation with Patrick Leterme | Aimez-vous Schönberg ?

This year we celebrate Arnold Schönberg's 150th birthday, the perfect opportunity to shine a new light on this 20th-century composer who was a pioneer. Was he a radical innovator or did he in fact stay true to German Romanticism? We discover the many aspects of Schönberg's oeuvre in this conversation with Patrick Leterme.

You have been active as a composer, musical director and pianist for many years. You are also known for making classical music accessible to a large audience, as you did in the series Je Sais Pas Vous on the Belgian radio station Musiq3. When did you first discover the music of Schönberg?

I studied at the conservatory in the 2000s and encountered Schönberg there for the first time. The first thing I learned was the new compositional system he had invented: dodecaphony (twelve-tone technique). Schönberg had the image of a theoretical musician. This theoretical aspect and his technical system masked many other elements, such as the expressive side of his music. His students Anton Webern and Alban Berg claimed he was a composer of the twelve-tone technique, and Schönberg was part of the Second Viennese School. As often, the fate of the artistic work escapes its creator.

What does dodecaphony entail? How would you explain it to people with no musical training?

The dodecaphonic system attaches equal importance to all 12 notes of the Western system (from do to si, including the black keys of the piano). So the composer has to use all 12 notes before he can reuse any of them in his composition. This is to break with the tonal system (in which one tone, the tonic, is more important than the others), the universal musical grammar at the time. It is as if a painter would decide to use every primary colour on the same surface of the canvas, in the same proportions. Or like a writer who would use every vowel the same number of times in a novel. It is a technical process.

Schönberg adopted this rule for the choice of notes, but when it came to the other parameters, he was still very romantic. He constructed his musical phrases as people were still composing them at the end of the 19th century. The dodecaphony is easy in theory to perform, but to compose a musically interesting work, you need a serious musical background. And even more talent and genius.

Schönberg believed that he had solved the problems in the German musical tradition with his twelve-tone technique, but it did not have the impact he had hoped for. For that, it was too conceptual and technical. But in what respect was his approach fruitful?

When I listened to Schönberg's works again and reflected on his legacy, my vision really changed when I understood what he contributed to music history. The generation after Schönberg, led by Pierre Boulez, developed serialism by extending the principle of the twelve-tone technique to all musical dimensions (dynamics, duration, etc.). This was considered a dead-end street by many.

Later generations responded against this movement by returning to simpler musical principles. American minimalism and spectralism, perhaps the most important musical styles in Europe and the United States from the 1960s and 1970s onwards, were both a reaction to Schönberg's legacy. But the twelve-tone technique was a necessary step to break with tonal music. It is hard to imagine that minimalism and spectralism (non-tonal music either) would have emerged by directly opposing Romantic music.

On the other hand, Schönberg was not fruitful in his intention for he believed that he could transform the musical ear and that people would one day whistle twelve-tone melodies in the streets. That was his dream.

Schönberg's work developed at a time when innovation was emerging in all the arts, especially in cities such as Berlin, Vienna, Paris and Brussels. Influences from literature, painting, music and architecture merged into a new artistic language.

Schönberg spent his entire career in capital cities. In these cities, a search for expression traversed painting, architecture, literature and music. It was an urban culture, with no reference to the countryside.

The emergence of cabaret at that time is a reflection of that urban culture. It is urban, carnal music mixing all kinds of art forms. Schönberg was also musical director of the first German cabaret, Überbrettl, in Berlin.

This context is strongly reflected in his work Pierrot lunaire: a mixture of cabaret, poetry and symbolism, among others. The first line of Pierrot lunaire is "Den Wein, den man mit Augen trinkt" (The wine we drink through the eyes), which perfectly summarises symbolist poetry. It shows Schönberg's desire for colour and expression.

He was not only influenced by various art forms, but was an amateur painter himself. His paintings impressed artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc and Oskar Kokoschka. How do you think his painting relates to his musical compositions?

When I looked at his paintings, I felt that he is more free when he paints. He is more free because he is not trying to make a career out of his paintings. They show a passionate, romantic person with a lot of pathos. This is present as well in his music, but somewhat obscured by his theory. Such freedom can be heard in early works like Kammersymphony No 1 and Verklärte Nacht.

Both works Pierrot lunaire and Verklärte Nacht, op. 4 will be performed by Brussels Philharmonic during the festival. What’s so special about Verklärte Nacht?

Verklärte Nacht shows Schönberg's passionate, romantic side. The work is based on a poem by Richard Dehmel about a woman who reveals to her lover that she is pregnant by another man. The lover decides to accept the child as his own. Schönberg composed this music for a string sextet, which is quite unusual for the genre [during the festival you will hear the version for orchestra, red.].

In this work, Schönberg wanted to reconcile the two protagonists of the biggest musical dispute of the time: Johannes Brahms and Richard Wagner. In Verklärte Nacht, he reconciles Wagner's fire and new chords with Brahms' architectural mastery.

Baritone Samuel Hasselhorn and Julien Libeer will perform the work Das Buch der Hängenden Gärten, op. 15.

This work carries us into a symbolic realm that is almost abstract. Although there is a story, we are overwhelmed by the colours without really being able to follow the storyline. Expression becomes more important than events. Although Schönberg does not rely on traditional chords, you can feel his passionate, lyrical and romantic side.

We are celebrating Schönberg's 150th birthday this year. Why is it important to dedicate a festival to this composer?

Now we have enough distance to see Schönberg in a new light. The aesthetic conflict was so great in Schönberg's era that it took a long time to see things from another perspective. Breaking with tonality is no longer as shocking as it was back then. It is time to deconstruct Schönberg's posthumous image and (re)discover his oeuvre.

The festival programme covers the whole scope of his work. If you want to summarise someone's life, you have to show it in its entirety. And the programme reconnects Schönberg with his own desire: to be part of the continuation of a musical tradition.

And programming his works in Flagey means presenting them in their proper historical context [the Flagey building was designed during the same period as Schönberg's productive years, red.].

Aimez-vous Schönberg? (Do you love Schönberg?) Surprise yourself and formulate your proper answer through the discoveries during the festival, including an exhibition and exceptional performances of his work.